This is the third installment in an ongoing series examining the Old Norse Lay of Atli (Atlakviða) strophe by strophe.

My translation of the Lay of Atli, Strophe 3:

Atli sent me to ride hither on an errand,

the horse champing at the bit

through the unknown Mirkwood

to bid you, Gunnar,

that you come to the bench

with helmets gripping the hearth

to seek the home of Atli.

The structural positioning of this strophe serves as a prelude to the dramatic irony that unfolds upon the Giukungs' arrival at Atli's hall. It bears noting, for those perhaps laboring under misconceptions perpetuated by certain fantasy literature, that "Mirkwood" functions merely as a conventional Old Norse territorial demarcator — a generic toponym applied to any wooded border region between estates, rather than designating any specific forest.

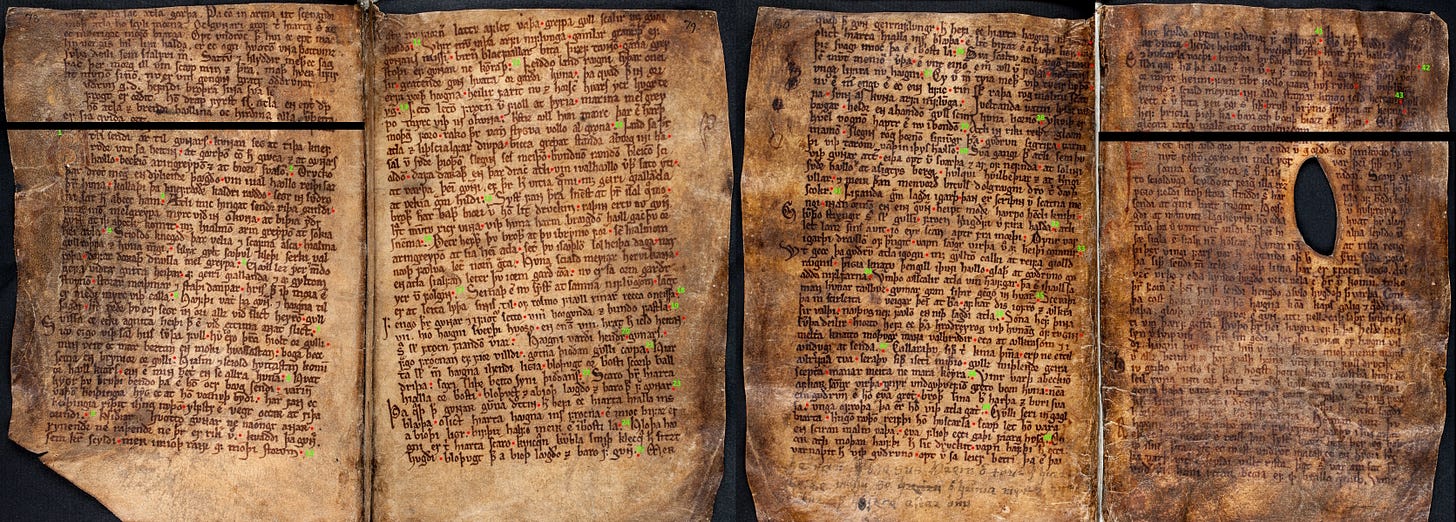

There are 43 strophes in the Atlakviða. The entire work is compressed within a mere three pages of the Codex Regius, an achievement of spatial efficiency that could only have been accomplished through the deliberate omission of what we, in our modern typographical sensibilities, would consider essential white space around line breaks. While contemporary readers might find this absence of familiar visual architecture somewhat destabilizing, the Atlakviða's inherent readability was preserved through its metrical and alliterative scaffolding.

In matters of translation, direct consultation of the manuscript often proves invaluable, particularly when confronting passages where normalized editions make assumptions regarding vowel mutations or scribal errors. Thomas Dalton, my academic sibling, annotated the manuscript to divide the strophes, and he has kindly given his permission for me to post it here. What a rockstar Thomas is, just look at his work:

The dense, continuous flow of text in the manuscript suggests a medieval reading practice more attuned to oral performance than silent study. In this light, the Codex Regius stands as a testament to how the physical constraints of manuscript production shaped the way these ancient verses were transmitted and received. Thomas Dalton's careful strophic annotations thus serve as a crucial bridge between these two worlds of reading, allowing us to appreciate both the economy of medieval scribal practice and the intricate formal structures that made such economy possible.